Details

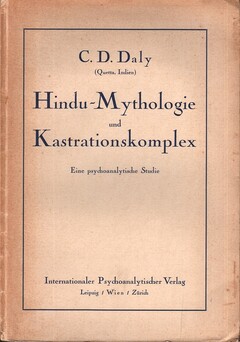

| Autor | Daly, Claud Dangar (884–1950) |

|---|---|

| Verlag | Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, Wien |

| Auflage/ Erscheinungsjahr | 1927, Erste Buchausgabe |

| Format | Gr.-8° |

| Einbandart/ Medium/ Ausstattung | OLwd. mit goldgeprägtem Titel |

| Seiten/ Spieldauer | 60 Seiten, 2 Bl. |

| Abbildungen | 1 Bildtafel |

| SFB Artikelnummer (SFB_ID) | SFB-001330_AQ |

(Grinstein 6392), Erste Buchausgabe. - Sonderabdruck aus "Imago, Zeitschift für Anwendung der Psychoanalyse auf die Natur- und Geisteswissenschaften". Hrsg. von Sigmund Freud, Band XIII, 1927.

Zu dieser Arbeit

»Ein flüchtiges Studium der Zeremonien und Riten der Hindu und der verwandten Völker ist ausreichend, um zu zeigen, daß sie unter kollektiven Zwangsvorstellungen leiden, die in vieler Hinsicht denen gleichkommen, die wir bei den europäischen Zwangsneurotikern zu beobachten gewöhnt sind. Ein früherer Autor hat die Aufmerksamkeit bereits auf die Tatsache gelenkt, daß ihre Charakterzüge fast ausschließlich dem analen Reaktionstypus angehören.«

Claud Dangar Daly

Aus dem Inhalt

Einleitung

- Allgemeines und Psychologie der Hindu

- Die Abspaltung

- Kurze Analyse gewisser Bestandteile des Hinduismus

- Die Rückkehr zu den analen Interessen und die Fixierung in ihnen als Resultat der Kastrationsangst

- Ambivalente Einstellung zu den weiblichen Genitalien

Die hinduistische Göttin Kali

- Allgemeine Beschreibung der Göttin und ihrer Attribute

- Lha-Mo, das tibetanische Gegenstück zu Kali

- Bemerkungen zu einer hinduistischen Abhandlung über Kali

Der Kalisymbolismus

Der Penisneid

Schluß

- Die Todesangst der Hindu

- Kali, die Schlachtenkönigin

- Das „Unheimliche" und das „Geheimnisvolle"

- Der Menstruationskomplex

Über den Autor und die vorliegende Arbeit

Daly, Claud Dangar (1884–1950), lieutenant-colonel and psychoanalyst

»(...) Freud took an androcentric monotheism for granted. He was more than puzzled by the Hindu pantheon, and expressed openly how bored he was by Indian visitors, such as the author Rabindranath Tagore, the philosopher Surendranath Dasgupta, and the linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji. In a letter to Romain Rolland, written in 1930, Freud commented on this writer’s enchantment with Indian culture: ‘I shall now try with your guidance to penetrate into the Indian jungle from which until now an uncertain blending of Hellenic love of proportion, Jewish sobriety, and philistine timidity have kept me away.’ (Hartnack 2001:138) In his correspondence with Freud, Bose explicitly pointed to the importance of the maternal deities in his culture. Other Indian psychoanalysts even criticized classical Freudian psychoanalysis for being a product of a ‘Father religion or Son religion’. This is especially ironic, since Freud had deconstructed the role of religion, and was – unlike his Indian colleagues – rather secular. Freud derived his insights primarily from his therapies with highly educated upper middle-class Viennese women patients who lived in patriarchically structured nuclear families. These women often envied their brothers and other men for being able to make use of their education and for enjoying social freedoms. Freud’s notion of penis envy thus also reflects the social situation of his women patients in early twentieth century Vienna. Bose, on the other hand, treated mostly upper-caste westernized Bengali Hindu men. Among them he had discovered ‘a wish to be female’. He wrote to Freud in 1929: ‘The desire to be a female is more easily unearthed in Indian male patients than in European.’ (Sinha 1966:430) In analogy to Freud’s women patients in Vienna, these Bengali men were also hindered in their development – in their case by the realities of colonialism. It is likely that they envied Bengali women who were only indirectly affected by British domination. Moreover, femininity was represented by powerful goddesses and therefore associated with desirable traits. In Bengali joint families in the early part of the twentieth century, the biological father was only one of several patriarchal figures, and the biological mother just one of several maternal authorities, resulting in multiple sources of affections and emotional bonds as well as ‘hydra-like’ (Kakar 1982: 420) confrontations with authorities. The direction of aggression, too, differed in European and Indian texts and folkloric traditions. As A.K. Ramanujan (1983, p.252) pointed out, in Indian literature the aggressor is often the father and not the son, as in the classical Oedipus tale, because the father is jealous of his wife’s devotion to her son. It is therefore not surprising that Bose rejected Freud’s view of the transcultural universality of the Oedipus complex. In 1929, he sent him thirteen of his psychoanalytical articles, noting: ‘I would draw your particular attention to my paper on the Oedipus wish where I have ventured to differ from you in some respects.’ Bose claimed, for example, that its resolution is achieved by fighting and overcoming the father’s authority, and not by a submission to it: ‘I do not agree with Freud when he says that the Oedipus wishes ultimately to succumb to the authority of the super-ego. Quite the reverse is the case. The super-ego must be conquered ...The Oedipus [conflict] is resolved not by the threat of castration, but by the ability to castrate.’ (Hartnack 2001:148) The politics of psychoanalysis: imperial versus colonial conditions Until 1947, India was a British colony. This implied that the Indian Psychoanalytical Society had not only Indian, but also British members. For example, Lieutenant Owen Berkeley-Hill, a psychiatrist in the British army, used psychoanalysis to help British patients in the European Mental Hospital in Ranchi to adjust – or re-adjust – to life in a colony. In his cultural-theoretical writings, he also drew on psychoanalysis to legitimize British colonial rule. In an essay published in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis in 1921, he attributed to Hindus an anal-erotic personality structure, and ascribed highly positive characteristics to his English countrymen. Berkeley-Hill concluded that Hindus do not have a psychological disposition for leadership and thus need to be ruled. In addition to being obsessive-compulsive, they were also infantile, since ‘their general level of thought partakes of the variety usually peculiar to children.’ (Hartnack 2001: 52) Another officer in the Indian army, Claud Dangar Daly, also left no doubt about his value judgements on Hindus. In an essay published in Imago in 1927, he asserts that the character traits of the Hindus ‘are in many respects the same as we are accustomed to observe among European obsessive neurotics). Furthermore, in an article published in 1930 in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis, Daly wrote that ‘the Hindu people would have to make an effort to overcome their infantile and feminine tendencies …. The role of the British Government should be that of wise parents’. (Hartnack 2001: 67) (...)«

In: Freud on Garuda’s Wings Psychoanalysis in Colonial India,

by Christiane Hartnack, Donau-Universität Krems

Zum Erhaltungszustand

Unser Exemplar in der leinengebundenen Premiumvariante des Verlages und in sehr guter Erhaltung; keine Anmerkungen, Anstreichungen oder Stempel. - Selten.

Kommentare

Schreiben Sie den ersten Kommentar!

Neuer Kommentar

Bitte beachten Sie vor Nutzung unserer Kommentarfunktion auch die Datenschutzerklärung.